In Close to the Knives, David Wojnarowicz gives us an important and timely document: a collection of creative essays — a scathing, sexy, sublimely humorous and honest personal testimony to the “Fear of Diversity in America.”. From the author’s violent childhood in suburbia to eventual homelessness on the streets and piers of New York City, to recognition as one of the most provocative artists of his generation — Close to the Knives. When an HTTP client (generally a web browser) requests a URL that points to a directory structure instead of an actual web page within the directory, the web server will generally serve a default page, which is often referred to as a main or 'index' page.

David Wojnarowicz Close To The Knives A Memoir Of Disintegration Pdf

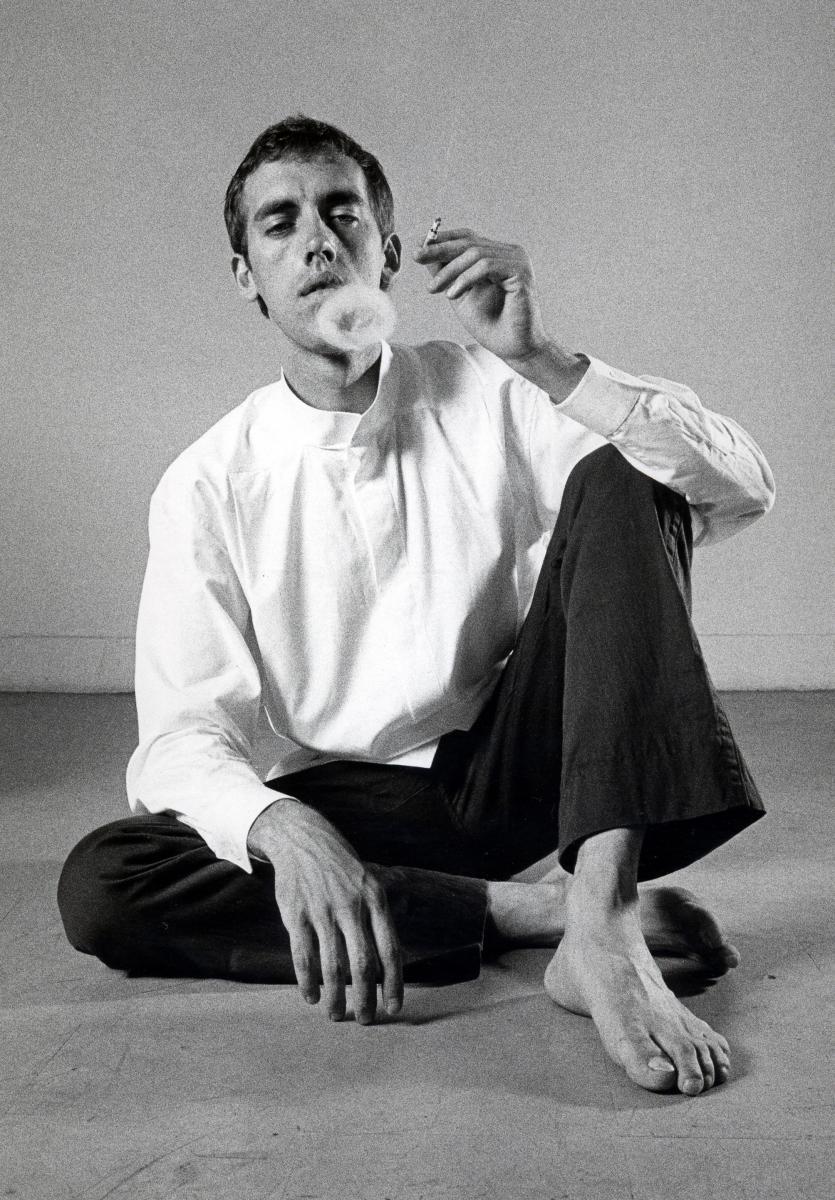

David Wojnarowicz, 1981

By Emily Colucci

In his essay, “Living Close to the Knives,” on the death of his lover and artistic mentor Peter Hujar, a renowned New York photographer, David Wojnarowicz explains, “and his death is now as if it’s printed on celluloid on the backs of my eyes.”1 Moments after Hujar’s death from AIDS-related complications on November 26, 1987, Wojnarowicz, a multidisciplinary artist, attempted to represent Hujar’s death through various mediums. First, with a super-8 camera, Wojnarowicz filmed Hujar’s body on his deathbed. Then, Wojnarowicz photographed individual parts of Hujar’s lifeless form, including his hands, feet, and face. Beyond the visual mediums, Wojnarowicz also wrote about his witnessing of Hujar’s death both in his essay “Living Close to the Knives” and his personal diaries. Wojnarowicz, who made a career out of depicting moments that were silenced by hegemonic and heteronormative society, such as his queer sexuality and childhood abuse, asserts a public statement of his private loss of Peter Hujar, who he calls “a teacher of sorts for me, a brother, a father.”2 As a public and political statement, Wojnarowicz’s use of the images of Hujar dead renders a different perspective on the AIDS crisis, which has diminished in public discourse in recent years. Although the AIDS epidemic claimed the lives of many others, including IV drug users, there has not been enough public recognition of the private losses within the gay community. Even queer theorists who point out the absence of a public recognition of the losses from AIDS seem to only focus on the lost narrative of AIDS activism and political collectivities. Taking Ann Cvetkovich’s ideas from An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures on the importance of archives in preserving not only queer knowledge but emotions, Wojnarowicz’s use of the moment of Hujar’s death from AIDS through various mediums creates an affective space for representing queer intimacies through a melancholic struggle with loss. Yet, the archive extends beyond each singular representation into a collective public archive of feeling and looking backward that could be politically generative.

The creation of a public statement from a private loss such as Wojnarowicz’s loss of Hujar and the preservation of the bonds that remain become necessary due to the homophobia and silence in society surrounding the AIDS crisis. Because of heteronormative society’s inability to publicly grieve for the deaths of countless gay men and others from AIDS, the insertion of private memories into the public discourse becomes a means of subversion. As David L. Eng, in his article “The Value of Silence,” states, “the loss—indeed, the refusal—of a public language to mourn a seemingly endless series of excoriated, dead young men triggers the absolute need to imagine a discourse of identification that could mean anything other than silence, isolation, self-abasement and death.”3 With this at stake, many in queer culture feel the creation of their own public statements on private loss and grief reflect this need. Wojnarowicz himself supported the solution of making the private public in order to subvert silences. In his essay “Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell,” which appeared in the catalogue for the Artists Space AIDS-related exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing creating a scandal with the National Endowment for the Arts, Wojnarowicz declares, “to turn our private grief for the loss of friends, family, lovers, and strangers into something public would serve as another powerful dismantling tool.”4 In An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, Cvetkovich supports a similar creation of public statements from private emotions. Since many traumatic events, including the witnessing of AIDS-related deaths, often leave behind no records due to the difficulty in finding a language for loss and grief, this trauma “puts pressure on conventional forms of documentation, representation, and commemoration, giving rise to new genres of expression, such as testimony, and new forms of monuments, rituals, and performances that can call into being collective witnesses and publics.”5 These new forms of documentation and representation also emphasize making the private—experiences, sexualities, and losses surrounding AIDS—public, countering the lack of a hegemonic and heteronormative language for the loss of homosexual attachments.

Untitled (Peter Hujar), 1989, by David Wojnarowicz

As a means to turn private grief and trauma into a public documentation, Cvetkovich suggests the use of archives of queer feelings to preserve the history of gay, lesbian, and queer experiences, including losses from AIDS. Rather than strictly historical documents, Cvetkovich stresses that archives should contain emotional history as well as tangible knowledge.6 In thecase of AIDS, many of these queer intimacies, sexualities, and activism are extremely difficult to record. Yet, there is an increasing need to preserve these experiences for public record before they are lost. The practice of archiving the feelings and affects of queer subjects, such as Cvetkovich’s oral history of AIDS activism, “counters the invisibility of and indifference to feelings of loss by making them extravagantly public as well as building collective cultural practices that can acknowledge and showcase them.”7 Similar to Cvetkovich’s insistence of a queer archive of feelings, Wojnarowicz represents the moment of Hujar’s death through various mediums in order to construct an archive of this one moment, which he called the most important of his life.8 Though Wojnarowicz’s images and descriptions of Hujar’s death are terribly difficult to behold, the archive he assembles corresponds with Cvetkovich’s declaration that archives of trauma “must enable the acknowledgment of a past that can be painful to remember, impossible to forget, and resistant to consciousness.”9 Wojnarowicz’s archive of Hujar’s death involves a constant revisiting and reworking of both the nature of his loss and his bond with Hujar, allowing for the preservation of a type of queer intimacy beyond death.

Wojnarowicz’s loss and struggle with Hujar’s death would often be classified as mourning, which queer theorists such as Douglas Crimp have combined with militancy to combat the AIDS crisis. Focusing on the AIDS crisis and the enormity of queer deaths, many queer theorists have applied Freud’s seminal essay “Mourning and Melancholia” to gain insight into loss and mourning in the AIDS epidemic. In “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud defines mourning as “the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction.”10 Careful not to pathologize those subjects in mourning, Freud explains the process of mourning as the libido’s withdrawal from the lost object.11 This withdrawal of the libido from the lost object is not a quick process, but is “carried out bit by bit, at great expense of time and cathectic energy, and in the meantime the existence of the lost object is psychically prolonged.”12 In his essay “Mourning and Militancy,” Douglas Crimp employs the idea of mourning to suggest a combination of mourning and militancy in the AIDS activist movement. Even though he prefers mourning rather than melancholy to address the public losses for gay men during the AIDS crisis, Crimp also indicates several contrasting points with Freud’s definition of mourning, including the social interference with mourning in the loss of gay men and the possibility that the grieving men may be subject to a fate similar to those they mourn.13 Aside from Crimp’s examples, another disparity arises when the libido does not withdraw from the lost object, as with Wojnarowicz and Hujar, which may give reason to turn away from mourning as a politically generative force. Download dell keyboards driver. While there is no question Wojnarowicz mourns the loss of Hujar, it can perhaps be understood that Wojnarowicz experiences something greater than mourning when considering the repeated revisiting of Hujar’s death in a variety of mediums. In “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud notes that eventually “when the work of mourning is completed the ego becomes free and uninhibited again.”14 This concept of mourning presumes an end to the mourning of the lost object, yet in some traumatic losses, such as witnessing the death of a loved one from AIDS, the work of mourning does not seem to correspond fully to this conclusive end. For Freud, even though the work of mourning is difficult, “respect for reality gains the day.”15 However, what happens when reality does not take control and the affective relationship with the lost object is not entirely rejected?

With these incongruities with mourning and the creation of an archive from a loss in the AIDS crisis, it may be necessary to understand Wojnarowicz’s manipulation of his loss as a politically generative work of melancholy rather than strictly mourning, even with the problematic pathological definition of melancholy. In “Mourning and Militancy,” Douglas Crimp hesitates to use the term melancholy for the witnessing of the loss of gay men from AIDS, because homosexuality had been pathologized by psychology in the past.16 However, other queer theorists, such as David L. Eng and David Kazanjian in the introduction to Loss: The Politics of Mourning, have rejected melancholy as a pathology and investigated Freud’s notion of melancholia in order to inform the work of loss and memory specifically in regard to activist cultures. According to Eng and Kazanjian, melancholy directly contrasts the problematic finality of mourning. In Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia,” melancholia occurs when the lost object is taken into the ego, rather than the libido becoming withdrawn from the object, and the ego becomes “judged by a special agency, as though it were an object, the forsaken object.”17 While the loss of a loved one or, most likely in the case of the AIDS crisis, many loved ones does not necessarily relate to this antagonistic relationship with the lost object, melancholy maintaining the lost object alive within the ego certainly permits a frequent reworking of the past. According to Eng and Kazanjian, Freud’s account of melancholia can be understood as an “enduring devotion on the part of the ego to the lost object.”18 While Freud’s conception of mourning essentially buries the past, melancholy allows for a reworking and reinterpreting of the past in the present. In “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud describes that “countless separate struggles are carried on over the object” in melancholia.19 The ability to reinterpret the past through countless melancholic struggles in the present relates to Wojnarowicz’s use of various representations to memorialize the experience of witnessing Hujar’s death from AIDS. Through these apparently melancholic reinterpretations of Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz is able to present “a continuous engagement with loss and its remains.”20 With the unique characteristics of each medium, from film to photography to writing, Wojnarowicz presents a public archive of the traumatic moment—keeping Hujar’s memory alive in the process.

David Wojnarowicz Close To The Knives Quotes

Self-Portrait (with String around Neck), 1980

Analyzing the individual representations in Wojnarowicz’s archive chronologically, the first medium Wojnarowicz employed was film, which has emerged for many AIDS activists as a means to record the memories of the dead. Unlike many of the other AIDS activists, who have employed film in a manner to preserve the living moments of those who died, Wojnarowicz literally films the moment after Hujar’s death. After Hujar’s final breath, Wojnarowicz “closed the door and pulled the super-8 camera out of [his] bag and did a sweep of his bed: his open eye, this open mouth, that beautiful hand with the hint of gauze at the wrist that held the IV needle, the color of his hand like marble, the full sense of the flesh of it.”21 After Hujar’s death in 1987, Wojnarowicz aspired to make an entire film about the death of Peter Hujar and his own process of grieving. While he would never complete this film, there remains an approximately four-minute silent black-and-white segment with the deathbed footage of Hujar combined with clips of beluga whales swimming. The video ends with an actor, as Hujar, being passed among a line of men in a portrayal of Hujar moving on in death. Many AIDS activists have also revealed the importance of film as a medium for memories and for political causes, yet they seem to utilize video in a different manner than Wojnarowicz. In her article “Video Remains: Nostalgia, Technology, and Queer Archive Activism,” Alexandra Juhasz discusses what film can add to queer archive activism referring to her own 2004 film Video Remains, which includes footage of her friend Jim before he died of AIDS.22 Allowing her to capture Jim alive, Juhasz sees film as a nostalgic rather than a melancholic object. Compared with Juhasz’s analysis of Video Remains, film for Wojnarowicz may be more melancholic than nostalgic due to the difference between showing an AIDS patient alive and an AIDS patient dead. Juhasz describes film as nostalgic, an “attempt to hold onto time, given its inevitable loss.”23 Juhasz relegates melancholy and mourning to the primarily private realm in comparison to nostalgia, which, to her, seems to work towards social change.24 In comparison, Wojnarowicz’s video of Hujar’s silent and still body is a definite melancholic object, intensely private, yet its use in the film medium can also be public. Contrasting with footage of Jim alive, Wojnarowicz is able to hold onto a memory of Hujar, yet he does not desire to return to the image of death that the footage portrays. Even though their definitions of melancholia, nostalgia, and video may be different, both Wojnarowicz and Juhasz understand the power of editing and montage in their films. In Video Remains, Juhasz weaves clips of female AIDS activists with the footage of her friend Jim, which adds a conversational aspect to the video of her dead friend. Regarding Video Remains, Juhasz believes “it is this conversation, through editing, that creates a sense of active nostalgic time from which, perhaps, new things might be produced.”25 Though not a nostalgic piece, Wojnarowicz’s use of editing in his film does interject a new perspective of intimacy to his project. The medium of film with editing provides a comparison between the movement of the bodies of the beluga whales in their tanks and the stillness of the body of Hujar on his deathbed representing a type of queer intimacy. In An Archive of Feelings, Cvetkovich highlights the appearance of certain queer bonds and intimacies between AIDS patients and their caretakers, which transcends sickness and normative sexuality. For Wojnarowicz, who was also Hujar’s caretaker, his representation of Hujar’s body in death reveals a queer intimacy that appears even past death. In her discussion of queer intimacies, Cvetkovich suggests that these queer moments between AIDS patients and their caretakers might create new political realms.26 Using the movement inherent in film and the qualities of editing, the slow swimming of the beluga whales interspersed with Hujar’s body allows for an intimate and sensual focus on the body that appears in all of Wojnarowicz’s representations of Hujar. As Cvetkovich describes, “cumulatively, these AIDS caretaking memoirs add to queer representations of sexuality by finding eroticism and affect in physical acts that occupy a far wider range than genital sexuality, and in relationships that are just as intimate as those between families, lovers, or friends.”27 While watching Wojnarowicz’s film, a certain profound eroticism in the combination of movement and stillness with the whales and Hujar emerges. With his pale and white form that, as Wojnarowicz observes, is exquisite like marble, Hujar’s body contains similarities with the whales and seems to have a similar grace even in his contrasting complete stillness. According to Wojnarowicz, the use of the beluga whales was inspired by his observation of their “pale, almost gray-white bodies, streaming through the sun, luminous waters of a giant tank viewed from the side in a darkened building.”28 The comparison between the bodies of the beluga whales and Hujar creates a certain queer sensuality, as Cvetkovich observes. However, the comparison seems to be deeper than just their sensual forms for Wojnarowicz. He uses the whales as a symbol for Hujar’s grace and innocence that persists even in death. In his diaries, Wojnarowicz states, looking at the whales, “I think of Peter. I think of these whales. I think of sad innocence in the face of death and the turning of this planet.”29

The second medium that presents the moment of Hujar’s death is photography, which has often been defined as a melancholic object from figures such as Susan Sontag. In Close to the Knives, Wojnarowicz describes that after the super-8 camera, he used “the still camera: portraits of his amazing feet, his head, that open eye again.”30 Death photographs are already significant in regard to Hujar’s life since he photographed many subjects during his career who were either dead or close to death such as his famous Candy Darling on her Death Bed, depicting the Warhol superstar dying of leukemia. In On Photography, Susan Sontag defines photography as “to participate in another person’s (or other thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability.”31 For Sontag, photographs record a specific moment of time, which is lost immediately after the taking of the photographs and cannot be reacquired in real life. As a record of loss, photographs imbue a type of immortality to the subject, permitting the constant revisiting that is inherent in melancholy. Similarly, in Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss, Jay Prosser analyzes the loss inherent in the taking of a photograph: “photography is the medium in which we unconsciously encounter the dead . . . Photographs are not signs of presence but evidence of absence. Or rather the presence of a photograph indicates its subject’s absence. Photography contains a realization of loss.”32 Recording Hujar’s body in death from his feet to his face, Wojnarowicz’s photographs are blatant assertions of loss and the preservation of a moment of time that will never return. Embodying the inevitable passing of time, Prosser states distinctly, “photography is a melancholic object.”33 For Prosser, photography makes the understanding of loss possible and presents a reminder of the death of loved ones. Even though photographs record absences, they can also preserve beauty in unexpected places through the capturing of time. Susan Sontag observes, “this freezing of time— the insolent, poignant stasis of each photograph—has produced new and more inclusive canons of beauty.”34 Through the halting of time, as Sontag states, the photograph is able to be studied and characteristics of the subject, which may not appear beautiful to the observer’s naked eye, become apparent through the mediation of the camera.

Through the ability of photography to both record losses and freeze moments of beauty, Wojnarowicz’s photographs of Hujar preserve the unique beauty of Hujar’s body. Even though photography indicates an inevitable loss and absence, photographs can also depict beauty in unexpected places. As Wojnarowicz himself states, photography can be used in the “preservation of bodies.”35 Not conventionally beautiful, the photographs of Hujar do contain a sort of profound beauty, specifically regarding the tactile nature in the photographs of Hujar’s hands, feet, and bearded face. As Cvetkovich reveals in her analysis of lesbian caretaker memoirs, the queer intimacy of touch between an AIDS patient and a caretaker is another form of queer intimacy.36 Discussing Rebecca Brown’s The Gifts of the Body, Cvetkovich states, “being a witness to death is a profoundly physical experience . . . a matter of one body literally touching another body.”37 In the lesbian caretaker memoirs, touch figures heavily and the tactile nature of Wojnarowicz’s photographs work with this same concept. In their stillness, Hujar’s feet and hands appear nearly flawless as part of a marble statue and seem as if the viewer could imagine the feeling of the touch of his feet and hands. The photographs of his hands portray even the slightest freckles on the backs of his hands, adding to the intimate nature of the photographs. His face also contains a tactile quality with his dark beard covering his sunken cheekbones and thin face, which recalls the face of many gay men who have died similarly of AIDS during this time. His eyes, as evidenced by Wojnarowicz’s writing, are open, providing both a slightly eerie and astoundingly intimate vision of the death of a loved one. With these photographs, Wojnarowicz captures both Hujar’s enduring beauty and the arresting reality of death from AIDS. In his diaries, he writes on the side of one page, “I wish I could just touch your head, put my hands on your head.”38 As a type of mediated touch between Wojnarowicz and Hujar through the power of photography, these photographs present a queer intimacy through the tactile quality of Hujar’s skin. Preserving his body, similar to how melancholy keeps the object in the ego, Wojnarowicz’s photographs reveal a sensuality in these images of Hujar’s body, even in death.

The final representation in Wojnarowicz’s melancholic archive is writing, which appears in his essay “Living Close to the Knives” from his collection Close to the Knives and in his diaries. Many experiences in the essay are taken directly from his diaries, and, therefore, there remains a similarity to the content but not necessarily the style of the writing. Even though language may not be equipped to exactly mirror moments as profound as the death of Hujar, Wojnarowicz still finds power in using his own words to counter the enforced silence in society. Wojnarowicz believes that “to speak about the once unspeakable can make the INVISIBLE familiar if repeated often enough in clear and loud tones.”39 Eng also highlights the importance of the language of loss that flies in the face of heteronormative society’s loss of language for grieving homosexual attachments. In “The Value of Silence,” Eng states that “this is a language of loss that is arduously created against the conscripted loss of language.”40 In An Archive of Feelings, Cvetkovich also discusses the power of the written word in her analysis of the memoirs of lesbian caretakers. For Cvetkovich, the memoir is a powerful medium in order to explore emotions that may not be discussed in other media such as oral history: “memoir has the potential to explore emotional terrain that is harder to get at through interviews; the sanctuary of writing, its privacy and deliberateness, potentially offers the arena for emotional honesty.”41 Memoir allows the writer to put forth their emotions, including melancholy, in ways that are not easily accessed through other means. Regarding AIDS specifically, Cvetkovich sees the memoir as an essential tool for the archive of queer memories on the topic of the AIDS crisis, “providing gay men with a forum to articulate what it means to live in the presence of death and record their lives before it is too late.”42 As with the photographs and film, diaries and memoirs can preserve affective moments that can survive beyond the life of the writer or artist.

In Wojnarowicz’s written account of the moment of Hujar’s death, like the film and the photographs, he focuses on the beauty of Hujar’s body revealing a type of enduring queer bond. As Cvetkovich analyzes, written forms such as memoirs and novels “constitute the unusual archive necessary to capture the queer bonds and affects of activism and caretaking.”43 In his descriptions of creating the film and photographs of Hujar, Wojnarowicz uses terms for Hujar’s body such as “beautiful,” “amazing,” and the “full sense of the flesh” of Hujar’s hand.44 With these phrases, the sensuality that Wojnarowicz still finds in Hujar’s form extends even beyond death. Employing words as he had employed photographs and video, he captures the beauty and eroticism in Hujar’s body. Even in his explanations of his relationship with Hujar, he highlights the aesthetics of Hujar’s body. For Wojnarowicz, Hujar was “like a father, but was it really that, because I also saw him as sexual, handsome, beautiful mind, beautiful body, his was similar to mine, even with twenty years’ difference.”45 The relationship between Wojnarowicz and Hujar as both lovers and artists is articulated through a discussion of Hujar’s body, as represented in the other two mediums in his archive of Hujar’s death. After Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz observes the sight of Hujar on his deathbed and attempts to articulate the meaning of that moment of witnessing. Like the other examples, a blatant form of queer intimacy appears in his recalling of Hujar’s body. In “Living Close to the Knives,” Wojnarowicz states, “this body of my friend on the bed this body of my brother my father my emotional link to the world this body.”46 Even more than the simple physical beauty of Hujar’s body, the queer bond between Wojnarowicz and Hujar can be expressed in more theoretical terms due to the characteristics of written language to represent Hujar after he is gone. At the cemetery after Hujar’s funeral, in the same diary entry as Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz describes his perception that he can physically feel Hujar all around his own body. Even though Hujar no longer has a tangible form, Wojnarowicz explains, “he’s in the wind in the air all around me. He covers fields like a fine mist, he’s in his home in New York City, he’s behind me, it’s wet and cold but I like it.”47 Wojnarowicz’s queer bond with Hujar transcends both death and physicality, which can only be articulated in the medium of writing. Even though Wojnarowicz is able to maintain an archive of his queer intimacy with Hujar in the initial representations of Hujar’s death from AIDS, there remains a pervasive sense of frustration in his own ability to faithfully represent Hujar’s death. The term frustration in this instance reveals a mix of many conflicting affects— from shame to helplessness to intense sadness—that seem to only appear as a static frustration regarding the representation of Hujar’s death. This mix of affects appears similar to Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings, which are defined as negative affects that do not express any type of agency.48 These ugly feelings are “explicitly amoral and noncathartic, offering no satisfactions of virtue, however oblique, nor any therapeutic or purifying release.”49 Even though the film emerges as a melancholic object that preserves a moment of queer intimacy, Wojnarowicz himself was unhappy with the film’s progress. Regarding the film, Wojnarowicz states in his diaries, “The obsession with this film and the order of things—I get confused in these moments about why things don’t work when I want them to.”50 Using Ngai’s ugly feelings, the frustration Wojnarowicz feels with the film is noncathartic as evidenced by the film’s incompletion. According to Ngai, these ugly feelings “are defined by a flatness or ongoingness entirely opposed to the ‘suddenness.’”51 Moving to the photographs, Wojnarowicz writes, “I kept trying to get the light I saw in that eye.”52 This attempt to get the light in Hujar’s eyes may be an impossible task and yet Wojnarowicz continues to try to capture the light he perceives. Like the ugly feelings’ ongoingness, his frustration allows for a constant repetition in attempt to capture that light. However, the ugly feeling of frustration can perhaps be best illustrated in his written accounts of Hujar’s death. Although Wojnarowicz believes in the power of the written word to present new narratives that displace the silences of heteronormative society, he struggles with approximating the right expressions for Hujar’s death. In the beginning of a 1987 diary entry, he states, “I can’t form words these past few days.”53 His diaries are riddled with anecdotes about how he cannot use language to describe the event of witnessing Hujar’s death. In a moment of extreme frustration, he exclaims, “this is the most important event of my life and my mouth can’t form words.”54 This mix of emotions, which culminates in a strong frustration, points to a certain stasis in his inability to faithfully represent the loss of Hujar. However, even though frustration and other ugly feelings “are not likely to ignite revolutionary action or even mass resistance,” there may be possible political force in the questioning of the reason for Wojnarowicz’s inability to articulate the moment of loss.55 As Heather Love in Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History states, “rather, I would venture that this persistent attention to ‘useless’ feelings is all about action: about how and why it is blocked, and about how to locate motives for political action when none is visible.”56 Perhaps Wojnarowicz’s frustration with the representation of Hujar’s death could inform other mediums for creating a more complete public statement out of a private loss relating to the AIDS crisis or other traumatic experiences.

Through the use of Hujar’s death images in representing queer intimacies and affects both ugly and cathartic, there appears to be a type of looking backward related to the memory of Hujar’s death. Perhaps Wojnarowicz’s use of frustration and turn back to the past could be defined as a queer temporality similar to Heather Love’s Feeling Backward. Rather than a progressive activist vision, Wojnarowicz’s backward glance to the death of Hujar may be more of an affective and effective turn for activism than mere militancy, though his own rage is marked by a melancholic turn backward. Queer identity is usually discussed with progress in mind and a forward-looking trajectory. The emphasis on progress in queer political movements and cultures can be observed due to the narratives normally publicized, even in the AIDS crisis. Even with the deficit of AIDS-related representations, there seems to be a focus on AIDS activism and progressive movements. This narrative of AIDS activism is important and yet it continues the legacy of progress that denies some of the extremely painful past. As Love states, “we are in practice deeply committed to the notion of progress; despite our reservations.”57 However, queer theorists such as Love hypothesize that it may be better to look backward to the affects generated in the painful past. Turning away from this notion of progress, Wojnarowicz’s representations of death may be just as important politically as his militant collages and films for ACT UP. For Love, queers have always symbolized backwardness, giving this ability to recall the past through archives and other representations a decidedly queer definition.58 Love stresses, “rather than disavowing the history of marginalization and abjection, I suggest that we embrace it.”59 This embracing of backwardness can be applied to Wojnarowicz’s turn back to the painful memories of Hujar’s death in his archive of representation, which can both shed light on the painful experiences and losses of the past and highlight the particular parts of the present which need work. One of the ways in which to remember the difficulties of the past may be through the use of melancholy. Through Wojnarowicz’s archive of queer intimacies and affects, he employed melancholy to create “an ongoing and open relationship with the past—bringing its ghosts and specters, its flaring and fleeting images, into the present.”60 Like Wojnarowicz’s constant remembrance of Hujar, Love maintains, “resisting the call of gay normalization means refusing to write off the most vulnerable, the least presentable, and all the dead.”61

From the analysis of Wojnarowicz’s repeated use of Hujar’s deathbed images as a cohesive archive of queer intimacies and affects of frustration and rage, a melancholy turn backward can be defined as politically generative, revealing silences in both past experiences and contemporary society. Due to the archive’s look back to the ultimate painful loss from AIDS, Wojnarowicz’s representations do preserve a type of graceful tenderness and sensuality in their relationship. Even though his representations of Hujar are difficult and troubling, they may be able to inform future AIDS activism, which has been lost in recent queer politics. Wojnarowicz’s representations of Hujar may effect how AIDS is seen in the public memory today. In a recent New York Times article, “Lost to AIDS, But Still Friended,” about the use of social networking sites to preserve the memories of those who died from AIDS, many former and current AIDS activists insist that most 25-year-olds do not recognize ACT UP or do not know that there was a time when fear compelled many New Yorkers to read the obituary section before the front page during the AIDS crisis.62 As writer and director of the ACT UP Oral History Project, Sarah Schulman states, “there is absolutely no permanent social marker of the hundreds of thousands who died of AIDS in this country.”63 Even though AIDS activism is important to preserve, Wojnarowicz points out with his creation of an archive of queer intimacies and the use of his rage and frustration turning back to the death of Hujar, that activism occurred for a particular reason, the death of countless queer individuals. In his essay “Living Close to the Knives,” Wojnarowicz states, “all I can do is raise my hands from my sides in helplessness and say, ‘All I want is some sort of grace.’ And then the water comes from my eyes.”64 Perhaps in the creation of an archive of representations of Hujar’s death, revealing their queer intimacy beyond death and a turn backward through affects both ugly and militant, Wojnarowicz may acquire the grace he desires in his legacy.

Notes

1 David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (New York:

Vintage Books, 1991), 102.

2 David Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream: The Diaries of David

Wojnarowicz, ed. Amy Scholder (New York: Grove Press, 1999), 199.

3 David L. Eng, “The Value of Silence,” Theatre Journal 54 (2002): 88.

4 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 121.

5 Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public

Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 7.

6 Ibid., 249.

7 Ibid., 163.

8 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 103.

9 Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 241.

10 Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” The Standard Edition of the

Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916): On the

History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other

Works, 242.

11 Ibid., 243.

12 Ibid., 244.

13 Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October 51 (Winter, 1989): 9.

14 Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 244.

15 Ibid., 243.

16 Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 14.

17 Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 248.

18 David L. Eng and David Kazanjian, eds., Loss: The Politics of Mourning (Berkley:

University of California Press, 2002), 3.

19 Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 255.

20 Eng and Kazanjian, Loss, 4.

21 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 102.

22 Alexandre Juhasz, “Video Remains: Nostalgia, Technology, and Queer Archive

Activism,” GLQ 12, no.2 (2006): 319.

23 Ibid., 321.

24 Ibid., 322.

25 Ibid., 325.

26 Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 237.

27 Ibid., 223.

28 Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream, 204.

29 Ibid.

30 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 102.

31 Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Picador, 1973), 15.

32 Jay Prosser, Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss (Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 2005), 1.

33 Ibid.

34 Sontag, On Photography, 111–12.

35 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 142.

36 Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 214.

37 Ibid., 225.

38 Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream, 201.

39 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 153.

40 Eng, “The Value of Silence,” 89.

41 Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings, 210.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid., 237.

44 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 102.

45 Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream, 203.

46 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 103.

47 Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream, 103.

48 Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 3.

49 Ibid., 6.

50 Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream, 204.

51 Ngai, Ugly Feelings, 7.

52 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 102–03.

53 Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream, 199.

54 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 103.

55 Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 2007), 13.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid., 3.

58 Ibid., 6.

59 Ibid., 29.

60 Eng and Kazanjian, Loss, 4.

61 Love, Feeling Backward, 30.

62 Guy Trebay, “Lost to AIDS, But Still Friended,” New York Times, December 13

2009, ST1.

63 Ibid.

64 Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 103.

Close To The Knives David Wojnarowicz Pdf

Download the PDF here:

ASX CHANNEL: Peter Hujar

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

(© Peter Hujar & David Wojnarowicz, 2010. All rights reserved.)

Close To The Knives David Wojnarowicz

When an HTTP client (generally a web browser) requests a URL that points to a directory structure instead of an actual web page within the directory, the web server will generally serve a default page, which is often referred to as a main or 'index' page.

A common filename for such a page is index.html, but most modern HTTP servers offer a configurable list of filenames that the server can use as an index. If a server is configured to support server-side scripting, the list will usually include entries allowing dynamic content to be used as the index page (e.g. index.php, index.shtml, index.jsp, default.asp) even though it may be more appropriate to still specify the HTML output (index.html.php or index.html.aspx), as this should not be taken for granted. An example is the popular open source web server Apache, where the list of filenames is controlled by the DirectoryIndex[1] directive in the main server configuration file or in the configuration file for that directory. It is possible to make do without file extensions at all, and be neutral to content delivery methods, and set the server to automatically pick the best file through content negotiation.

If the server is unable to find a file with any of the names listed in its configuration, it may either return an error (generally 404 Not Found) or generate its own index page listing the files in the directory. It may also return a 403 Index Listing Forbidden. Usually this option is also configurable.

History[edit]

A scheme where web server serves a default file on per-subdirectory basis has been supported as early as NCSA HTTPd 0.3beta (22 April 1993),[2] which defaults to serve index.html file in the directory.[2][3] This scheme has been then adopted by CERN HTTPd since at least 2.17beta (5 April 1994), which its default supports Welcome.html and welcome.html in addition to the NCSA-originated index.html.[4]

Later web servers typically support this default file scheme in one form or another; this is usually configurable, with index.html being one of the default file names.[5][6][7]

Implementation[edit]

In some cases, the home page of a website can be a menu of language options for large sites that use geo targeting. It is also possible to avoid this step, for example by using content negotiation.

In cases where no index.html exists within a given directory, the web server may be configured to provide an automatically-generated listing of the files within the directory instead. With the Apache web server, for example, this behavior is provided by the mod_autoindex module[8] and controlled by the Options +Indexes directive[9] in the web server configuration files.

Close To The Knives By David Wojnarowicz

References[edit]

- ^'mod_dir - Apache HTTP Server'. httpd.apache.org. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ^ ab'WWW-Talk Apr-Jun 1993: NCSA httpd version 0.3'. 1997.webhistory.org.

- ^'NCSA HTTPd DirectoryIndex'. January 31, 2009. Archived from the original on January 31, 2009.

- ^'Change History of W3C httpd'. June 5, 1997. Archived from the original on June 5, 1997.

- ^'mod_dir - Apache HTTP Server Version 2.4 § DirectoryIndex Directive'. httpd.apache.org. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^'NGINX Docs | Serving Static Content'. docs.nginx.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^'Default Document <defaultDocument> | Microsoft Docs'. docs.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^'mod_autoindex - Apache HTTP Server Version 2.4'. httpd.apache.org. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^'core - Apache HTTP Server Version 2.4 § Options Directive'. httpd.apache.org. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

Wojnarowicz Documentary